Vaccines: Hundreds of years in the making, Millions of lives saved

We’ve probably all heard more about vaccines over the past three years than ever before.

Developing and delivering the COVID-19 vaccine was essential to our route out of the pandemic and back into normal life.

Yet vaccines are not something new, and they are not solely used to help us escape global health crises – they are there to prevent them.

In the first in a series, we’ll explore the origins of vaccines and how they work, previous success and current use, and touch on vaccine scepticism and safety.

Scroll down to read on or use the buttons to skip to different sections.

History

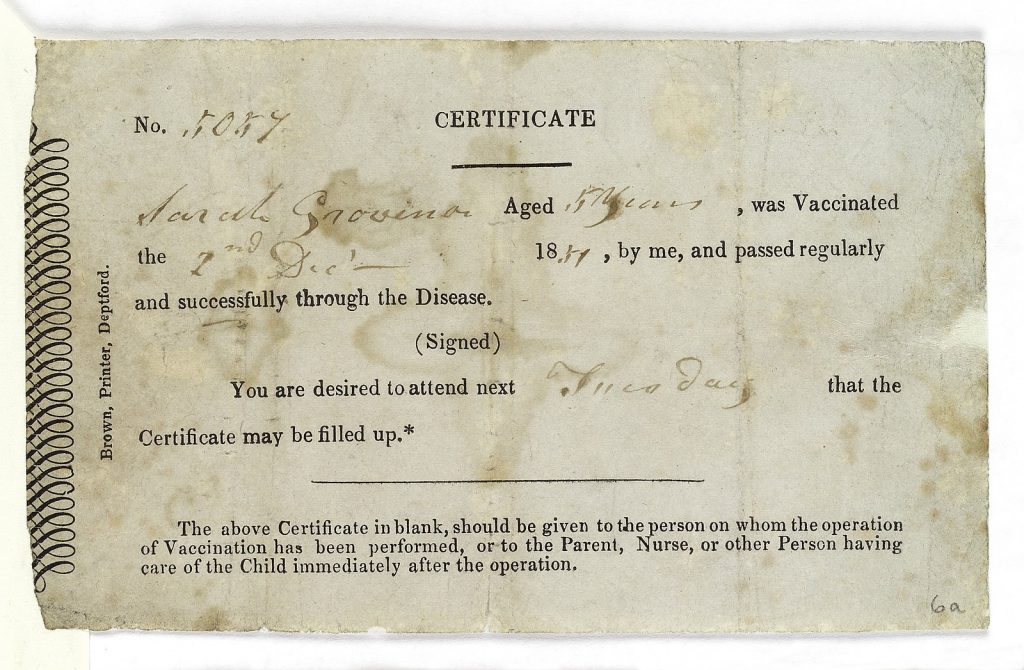

As far back as the 1400s, people all around the world were trying to prevent illness by deliberately exposing healthy people to small amounts of smallpox.

The practice became increasingly widespread, reaching Europe in the early 1700s.

Smallpox transmitted easily and became very widespread. 1 in 3 people who got it would die, and in the 18th century, it accounted for 400,000 deaths a year in Europe.

In 1796, English Physicist Edward Jenner created the first vaccine as we now know them. It used matter taken from a cowpox sore – a much less dangerous source – to provide resistance to smallpox.

The word vaccine takes its name from this discovery, with vacca being the Latin word for cow.

Years of extensive testing followed, and despite rumours spreading that it would turn you into a cow, by the early 1800s, it was shown to protect people effectively against smallpox.

Universal childhood vaccination followed in the US and UK in the 1840s-50s. Vaccination was compulsory in this country when it was introduced in 1854.

By 1971, the programme had been so effective that vaccinations in the UK were stopped as new cases were so few and far between.

The World Health Organisation declared smallpox eradicated in 1980, making it the first and, so far, only disease to be globally wholly wiped out through vaccination.

How they work

Vaccines teach the immune system how to recognise and fight off specific disease-causing germs.

As we’ve discussed, this was first done by exposing healthy people to the same virus they were targeting.

But, of course, vaccines have become much more advanced and considerably safer.

Modern vaccines contain weakened, inactive or, in some cases, synthetic versions of the disease. People are protected against the disease without getting ill first.

Our immune systems create a memory of how to fight off the virus and can then repel it again.

How long the vaccination protects us depends on the type of virus it is defending us against.

Some viruses – like flu or COVID-19 – can replicate quickly and create new strains of themselves. Others, like smallpox or measles, are more stable and don’t change. That’s why some vaccinations offer lifelong protection, and others must be ‘topped up’ or regularly boosted.

Successes

In the post-war years, routine vaccination of children became the norm. Polio, which once infected 1,000 children a day, was eradicated in Europe in the early 2000s (although it still exists in other parts of the world.)

Cases of other previously common diseases like diphtheria and meningitis are now sporadic in the UK due to mass vaccination.

More recently, in the first year of COVID-19 vaccinations, nearly 20 million deaths were prevented worldwide.

Every year, 3 million deaths are prevented worldwide by childhood vaccinations. But in 2021, nearly 1 in 5 children weren’t fully protected – the lowest rate in over a decade.

Scepticism and Safety

Scepticism and worries about vaccination have existed as long as vaccines themselves.

We’ve mentioned the ‘turn you into a cow’ rumours from the 1800s and other stories, tales, misinformation, and, in some cases, academic papers have suggested side effects or links to further illnesses.

In 1998, a published study suggested the Measles, Mumps and Rubella (MMR) vaccine caused autism. Despite being a small, uncontrolled speculative study, it was widely publicised, and vaccination rates began to fall.

More than a dozen large-scale studies followed. None showed any connection between the MMR vaccine and autism.

Eventually, the authors retracted their original study. Subsequent measles outbreaks in the UK and America were attributed to the fall in vaccination rates following the controversy.

The NHS website has an excellent section on vaccine safety, possible side effects, and the rigorous testing each jab must undergo before being used.

There is also a helpful video with a parent asking a GP why vaccines are safe for their child. Follow the link above or tap the image below to see the video and read more.

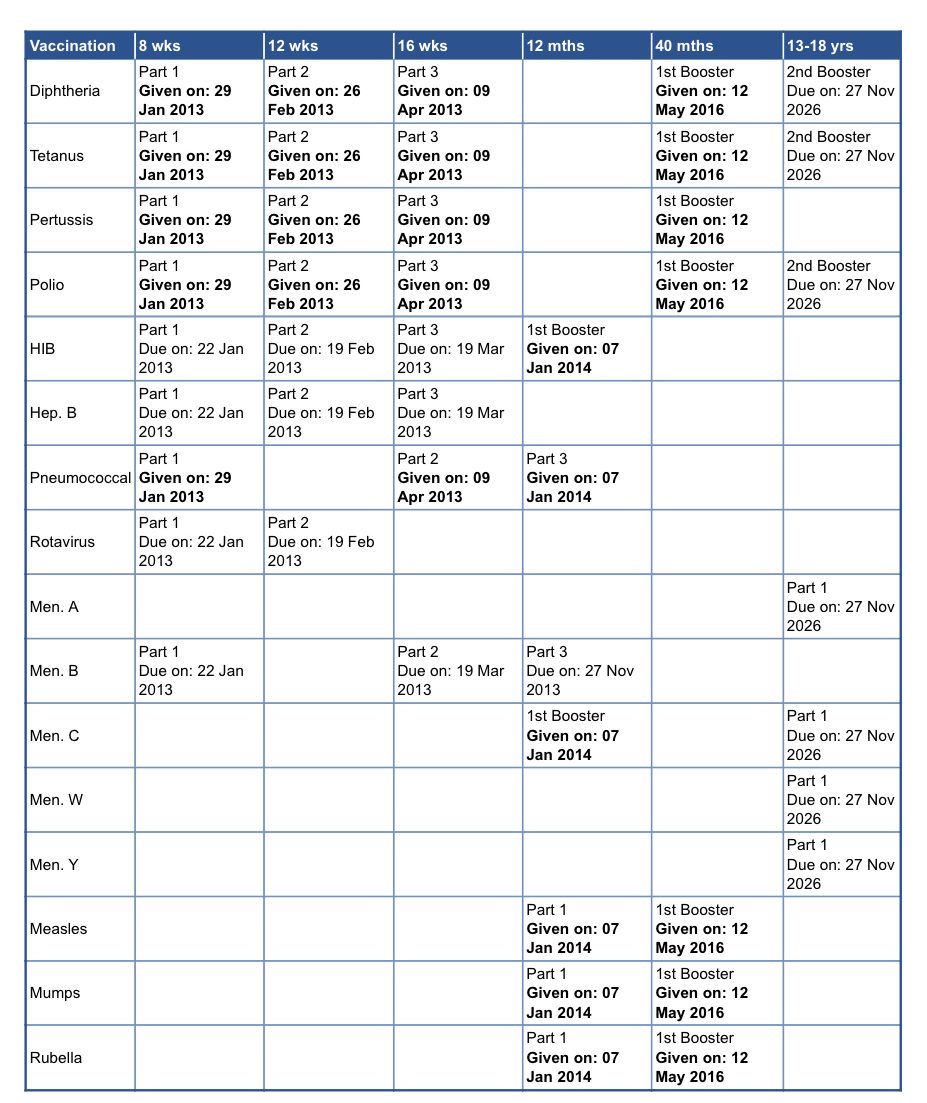

The NHS Vaccines schedule

The NHS vaccination programme protects a range of diseases from childhood, adolescence and into old age. The NHS routine childhood immunisation programme was revised in September 2023. This is the new complete immunisation schedule.

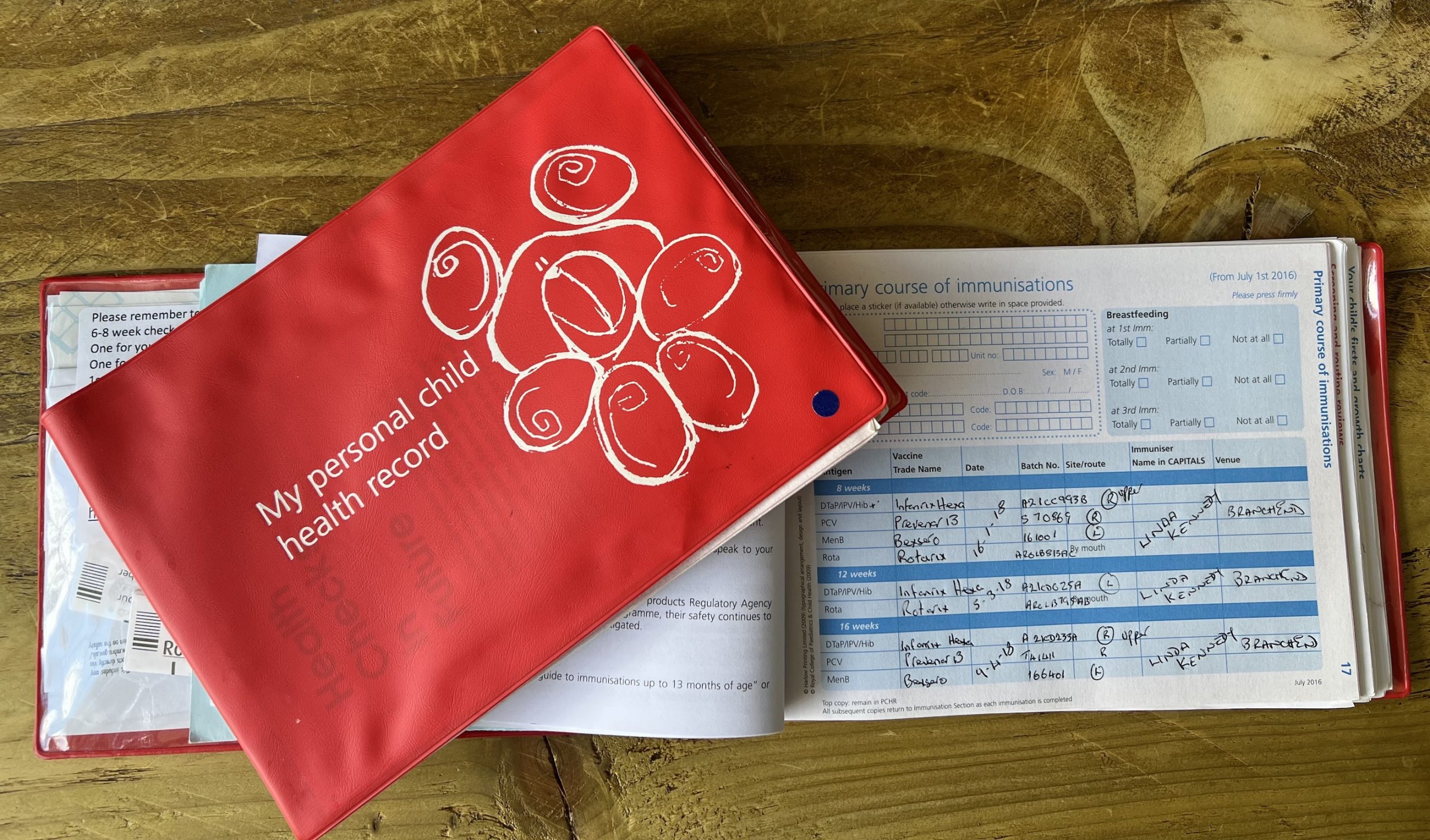

Your child’s vaccines should be recorded in their ‘red book’. Don’t hesitate to contact your GP practice if you are unsure or think your child may have missed a vaccination.

The NHS routine childhood immunisation programme was revised in September 2023. This is the new complete immunisation schedule.

| When | Diseases protected against | Vaccine given | Trade name | Usual site |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 weeks old | Diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis (whooping cough), polio, Haemophilus influenza type b (Hib) and hepatitis B | DTaP/IPV/Hib/HepB | Infanrix hexa or Vaxelis | Thigh |

| Meningococcal group B (MenB) | MenB | Bexsero | Left thigh | |

| Rotavirus gastroenteritis | Rotavirus | Rotarix | By mouth | |

| 12 weeks old | Diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, polio, Hib and hepatitis B | DTaP/IPV/Hib/HepB | Infanrix hexa or Vaxelis | Thigh |

| Pneumococcal (13 serotypes) | Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV) | Prevenar 13 | Thigh | |

| Rotavirus | Rotavirus | Rotarix | By mouth | |

| 16 weeks old | Diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, polio, Hib and hepatitis B | DTaP/IPV/Hib/HepB | Infanrix hexa or Vaxelis | Thigh |

| MenB | MenB | Bexsero | Left thigh | |

| 1 year old (on or after the child’s first birthday) | Hib and Meningococcal group C (MenC) | Hib/MenC | Menitorix | Upper arm or thigh |

| Pneumococcal | PCV booster | Prevenar 13 | Upper arm or thigh | |

| Measles, mumps and rubella (German measles) | MMR | MMRvaxPro or Priorix | Upper arm or thigh | |

| MenB | MenB booster | Bexsero | Left thigh | |

| Eligible paediatric age group | Influenza (each year from September) | (each year from September) Live attenuated influenza vaccine LAIV | Fluenz Tetra | Both nostrils |

| 3 years 4 months old or soon after | Diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis and polio | dTaP/IPV | Boostrix-IPV | Upper arm |

| Measles, mumps and rubella | MMR (check first dose given) | MMRvaxPro or Priorix | Upper arm | |

| Boys and girls aged 12 to 13 years | Cancers and genital warts caused by specific human papillomavirus (HPV) types | HPV | Gardasil 9 | Upper arm |

| 14 years old (school Year 9) | Tetanus, diphtheria and polio | Td/IPV (check MMRstatus) | Revaxis | Upper arm |

| Meningococcal groups A, C, W and Y | MenACWY | Nimenrix | Upper arm | |

| 65 years old | Pneumococcal (23 serotypes | Pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPV23) | Pneumovax 23 | Upper arm |

| 65 years of age and older | Influenza (each year from September) | Inactivated influenza vaccine | Multiple | Upper arm |

| 65 from September 2023 | Shingles | Shingles vaccine | Shingrix | Upper arm |

| 70 to 79 years of age (plus eligible age groups and severely immunosuppressed) | Shingles | Shingles vaccine | Zostavax (or Shingrix if Zostavax contraindicated) | Upper arm |

Selective immunisation programmes

| Target group | Age and schedule | Disease | Vaccines required |

|---|---|---|---|

| Babies born to hepatitis B infected mothers | At birth, 4 weeks and 12 months old | Hepatitis B | Hepatitis B (Engerix B/HBvaxPRO) |

| Infants in areas of the country with tuberculosis (TB) incidence >= 40/100,000 | Around 28 days old | Tuberculosis | BCG |

| Infants with a parent or grandparent born in a high incidence country | Around 28 days old | Tuberculosis | BCG |

| Children in a clinical risk group | From 6 months to 17 years of age | Influenza | LAIV or inactivated flu vaccine if contraindicated to LAIV or under 2 years of age |

| Pregnant women | At any stage of pregnancy during flu season | Influenza | Inactivated flu vaccine |

| From 16 weeks gestation | Pertussis | dTaP/IPV(Boostrix-IPV) |

Additional vaccines for individuals with underlying medical conditions

| Medical condition | Diseases protected against | Vaccines required |

|---|---|---|

| Asplenia or splenic dysfunction (including due to sickle cell and coeliac disease) | Meningococcal groups A, B, C, W and Y | MenACWY MenB |

| Pneumococcal | PCV13 (up to 10 years of age) PPV23 (from 2 years of age) | |

| Influenza | Annual flu vaccine | |

| Cochlear implants | Pneumococcal | PCV13 (up to 10 years of age) PPV23 (from 2 years of age) |

| Chronic respiratory and heart conditions(such as severe asthma, chronic pulmonary disease, and heart failure) | Pneumococcal | PCV13 (up to 10 years of age) PPV23 (from 2 years of age) |

| Influenza | Annual flu vaccine | |

| Chronic neurological conditions (such as Parkinson’s or motor neurone disease, or learning disability) | Pneumococcal | PCV13 (up to 10 years of age) PPV23 (from 2 years of age) |

| Influenza | Annual flu vaccine | |

| Diabetes | Pneumococcal | PCV13 (up to 10 years of age) PPV23 (from 2 years of age) |

| Influenza | Annual flu vaccine | |

| Chronic kidney disease (CKD) (including haemodialysis) | haemodialysis) Pneumococcal (stage 4 and 5 CKD) | PCV13 (up to 10 years of age) PPV23 (from 2 years of age) |

| Influenza (stage 3, 4 and 5 CKD) | Annual flu vaccine | |

| Hepatitis B (stage 4 and 5 CKD) | Hepatitis B | |

| Chronic liver conditions | Pneumococcal | PCV13 (up to 10 years of age) PPV23 (from 2 years of age) |

| Influenza | Annual flu vaccine | |

| Hepatitis A | Hepatitis A | |

| Hepatitis B | Hepatitis B | |

| Haemophilia | Hepatitis A | Hepatitis A |

| Hepatitis B | Hepatitis B | |

| Immunosuppression due to disease or treatment | Pneumococcal | PCV13 (up to 10 years of age) PPV23 (from 2 years of age) |

| Shingles vaccine | Shingrix – over 50 years of age | |

| Influenza | Annual flu vaccine | |

| Complement disorders (including those receiving complement inhibitor therapy) | Meningococcal groups A, B, C, W and Y | MenACWY MenB |

| Pneumococcal | PCV13 (up to 10 years of age) PPV23 (from 2 years of age) | |

| Influenza | Annual flu vaccine |

Extra vaccines may be offered to people with long-term health conditions or weakened immune systems.

As we said, the red book will have records of childhood vaccinations, as will the records held by GP surgeries. You may also see your jab history by logging into our online system.

If you believe you, your child, or someone else you care for has missed any vital vaccinations, please get in touch with your GP practice as soon as possible.